Grain to Glass: Pre-Prohibition Lager

Pre-Prohibition Lager is a style I've been wanting to brew for quite a long time. I love the notion of resurrecting a beer from the past and though I've never had any of the commercially available examples of Pre-Prohibition Lager, it sounds like it'll be absolutely delicious, so I decided it was finally time to brew one.

This is the first true lager I've ever brewed, and by "true lager" I mean I fermented cold and slow. Don't get me wrong, I'm not trying to be a snob here and get into the whole "if you ferment warm are you even really making a lager" thing -- I've made and had plenty of beers made with 34/70 or other "hybrid" yeasts fermented at higher temperatures and it can work great -- but this time around it seemed like it was high time to go through the slow and potentially finicky lager fermentation process as a rite of passage.

The Recipe

Some of you may just be here for the recipe, so here's the Brewfather link.

Additional comments:

- I added 4g of Fermaid O when pitching, and another 4.5g when fermentation was 30% complete.

- I wound up getting 76% efficiency instead of my predicted 65%, so the batch landed at 5.8% ABV, just shy of the 6% upper range for the style.

- I stored the beer in a purged, pressurized keg at 36 degrees F for a little over a week before carbonating -- supposedly this can help reduce the chance of getting any carbonic bite from the CO2.

I do hope you read on for some fun history and further discussion of the style!

What is Pre-Prohibition Lager?

The concept with Pre-Prohibition Lager, as you can probably guess from the name, is to recreate the style of the early American Lager (some refer to the lagers being made before Prohibition as "Pilsner-style beers") that reached its height of popularity in the 1870s and was a staple of the American beer scene until Prohibition went into effect in 1920.

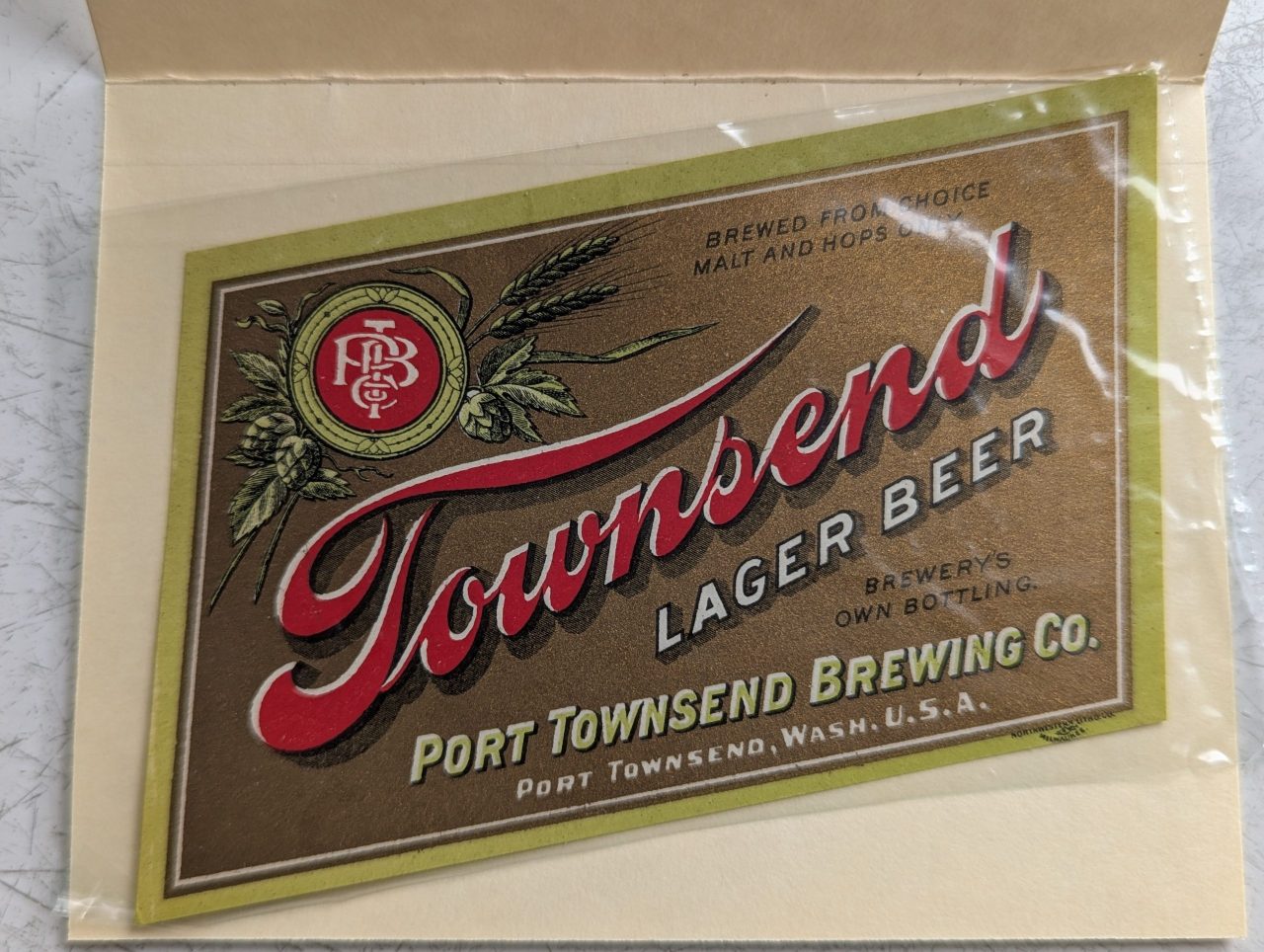

A pre-Prohibition beer label from Port Townsend Brewing Co. (ca. 1915)

A pre-Prohibition beer label from Port Townsend Brewing Co. (ca. 1915)

The major thing to know about the lagers that were made before Prohibition is that they bear only a passing resemblance to the lagers that came to dominate the beer market after Prohibition. Pre-Prohibition Lager is bigger, richer, more flavorful, and -- perhaps most notably -- more bitter and hoppy than modern American macro-lagers.

Craft beer aficionados are probably already aware of the decimating, homogenizing impact Prohibition had on American beer, with post-Prohibition beers, and specifically mainstream lagers, basically locked in an arms race to see who could create the least flavorful, most inoffensive beer possible.

If you're of a certain age you may even remember the "bitter beer face" Keystone Light commercials from the 1990s. Back then my local homebrew's response to this assault on flavorful beer was to sell a t-shirt with a big yellow 1970s-style smiley face on it, emblazoned with the words "Bitter Beer Face."

The 1990s is also when homebrewers started to experiment with approximating what American Lagers might have been like before Prohibition. Based on my research, interest in this style really picked up in the 2010s, with Pre-Prohibition Lager becoming an officially recognized BJCP style in 2015 in the "Historical Beer" category.

So just how historically accurate is our current take on what lagers might have been like before Prohibition?

"Not very" is probably the most accurate way to put it. It's not the fault of brewers or for lack of trying, but so much has changed with how barley is grown and malted, hops and hop cultivation, and yeast in the last 150 years, not to mention brewing practices, brewing equipment, and water, that even with historical accounts and recipes it's simply impossible to know how close we're getting to the actual flavor and character of these early American lagers.

We do know that German immigrants dominated the brewing industry in the United States in the 19th Century, and that they brought their brewing practices -- and their yeast -- with them. Most of the sources I've been reading point to John Wagner bringing lager yeast from Bavaria to the United States (specifically Philadelphia) in 1840, and he's credited with brewing the first lager beer in the United States. (To put this in some additional historical context, the "original Pilsner" -- Pilsner Urquell -- was first brewed in Plzeň in 1842.)

All this is to say that without a time machine we can't know exactly how a Pre-Prohibition Lager we brew in 2025 compares to those brewed before Prohibition, but it's fun to take a shot at it nonetheless.

A History of Ingredients

Barley

In terms of ingredients, let's talk about barley first, specifically two-row barley vs. six-row barley.

To address a couple of semi-common misconceptions (or at least oft-repeated anecdotes), two-row barley was grown and malted in the 1800s and was relatively readily available, despite what you may have read about two-row being hard to come by. You also may have heard the idea that brewers only used six-row when it was all that they had available since two-row was objectively better for brewing.

While there certainly could have been geographic and logistic reasons for brewers to use the type of barley that was most conveniently available to them, according to American Handy-Book of the Brewing, Malting and Auxiliary Trades published by Robert Wahl and Max Henius in Chicago in 1901, there was "... from the standpoint of American brewing, a decided advantage to be gained by employing the six-row barley." (pg. 451)

Additionally, according to analysis performed in Wahl and Hemnius's "Scientific Station for Brewing" lab:

"... the malts from such six-row barley are richer in diastatic and peptonizing power ... [and] the resulting worts are, at the same time, richer in desirable albuminoids … and the proteids formed, on the other hand, are much more readily precipitated by boiling or by subsequent cooling than in worts produced from malts from two-row barleys." (pp. 451-2)

Wahl and Hemnius continue:

"Hence, the six-row barley as it is grown in Wisconsin, Minnesota and Iowa is superior to the two-row barley as grown in Dakota, Montana, Utah, and the Coast, for light-colored beers, in the production of which large proportions of unmalted cereals like corn or rice are used. Such beers are, at the same time, more durable on account of the decreased amount of proteids they contain while the palatefulness and foam-holding capacity may be fully up to the standard of German beers, unless too much raw cereal is used …" (pg. 454)

Wahl and Henius also stated that six-row was better for malting due to the smaller size of the kernels.

With modern, highly-modified grains, the difference in diastatic power between two-row and six-row is negligible, particularly at the homebrew scale. Historically there may have been more of a difference, and this becomes important when (jumping ahead a bit here) considering the high percentage of adjuncts used in Pre-Prohibition Lagers. Higher diastatic power means more fermentable sugars can be extracted per pound of grain, and since flaked corn contributes (for all intents and purposes) no fermentables, the two ingredients work together nicely.

From a flavor perspective, two-row and six-row barley are rather different. I hadn't ever used six-row before brewing this beer so I was curious to taste the raw grains. To my palate the two-row has a smoother, rounder, and sweeter flavor, while the six-row has a rougher, "grainier" quality to it; different, but no less tasty, and I could already sense how it would work well with flaked corn.

Some Pre-Prohibition Lager recipes I've seen use a 50/50 split of two-row and six-row for the base grain, with the goal of, presumably, getting the best of both worlds, or perhaps smoothing out the rough edges of the six row. For my batch I went all-in with 100% six-row for the full historical experience, and honestly because I like the rough edges of the six-row.

All this is to say, I've read some modern takes on two-row vs. six-row that implied that brewers would have used six-row simply because it was more readily available, or that brewers would have preferred to use two-row whenever possible since it was better for brewing, so it was interesting to read an analysis from the period that, at least according to these brewing scientists, six-row was actually the superior grain for brewing due to the higher diastatic power and better-precipitating proteins -- particularly in light-colored beers with a high percentage of adjuncts -- when compared to two-row, creating a clearer beer with better foam retention.

Corn

Next, let's talk about corn and the use of adjuncts in general in pre-Prohibition brewing, since there seems to be a prevalent but ultimately incorrect notion that before Prohibition and the rise of massive macro-breweries, beer was all-malt, all the time.

The truth proves to be quite the opposite. The Beer Advocate Style Profile on Pre-Prohibition Lagers has a nice summary of some commercially available craft examples of Pre-Prohibition Lagers that ultimately misrepresent the history of the style.

Full Sail Brewing's Session Lager at one point described itself as "a classic all-malt pre-Prohibition style lager" (though this isn't the current description on their website); Lucky Bucket Brewing, which (perhaps ironically) hails from the Cornhusker State and -- full disclosure -- my home state of Nebraska, wrote that their pre-Prohibition lager "salutes a time when lagers had greater character and more distinct flavor, when beer wasn't full of the additives found in many of today's mainstream lagers" (they've also revised their marketing language); and Brooklyn Brewery's Brooklyn Lager was described as "a revival of Brooklyn's pre-Prohibition all-malt beers." Here again, the current description of Brooklyn Lager uses different language and given that it's dry-hopped, which is a technique that doesn't seem to have been used (or at least advertised) until right after Prohibition ended, the current version may have abandoned the pre-Prohibition style alignment.

At the other end of the spectrum of modern takes on Pre-Prohibition Lager is Live Oak Brewing's Pre-War Pils, which they advertise as:

"A 1912 German-American Recipe ... mashed with 35% corn grits. Immigrant German brewmasters created these beers to duplicate those from their homeland while using high protein American malts. These are the beers thirsty beer drinkers yearned for during prohibition -- "Pre-War" being the common way to refer to those times and those beers before Prohibition and before World War I. An authentic example of early American lager brewing as performed by the original German-American lager brewers."

Given the description, the high percentage of corn used in the mash, and an IBU of 32, Live Oak's Pre-War Pils is a more historically informed version of the style. According to the research I did while working on this beer at any rate, creating an "all-malt pre-Prohibition Lager" misses the point, and attempts to harken back to something was a rarity if it existed at all.

In the excellent article America's Founding Lagers: The Pre-Prohibition Landscape, Michael Stein, President of Lost Lagers, a Washington, DC-based beer history consulting firm (aside: could there be a cooler job?), writes about Master Brewer and educator Paul Kaiser, who was active from the 1880s until about 1950. The majority of Kaiser's pre-Prohibition recipes include adjuncts like grits, rice, sugar, and wheat flakes, and in his entire brewing notebook, only five of his recipes were all-malt.

Specifically, Kaiser's Pre-Prohibition Lager recipe -- called "Draught Beer 1912" -- is 46% pale malt, 42% grits, and 12% wheat flakes, for a total of 54% adjuncts, and used "two charges of California hops and one charge of New York hops."

Returning to our friends Wahl and Henius, they wrote, "At the present time [1901] corn, or products prepared therefrom, is used extensively in brewing, particularly in the United States." (pg. 467) Also included in their book are detailed steps for how best to prepare corn for brewing by removing the germ and husks, which then go on to become hominy, grits, corn meal, and flour.

Today of course we can just buy pre-gelatinized flaked corn and throw it in the mash. All hail modern convenience.

Hops

Collective wisdom is that the main hop used in pre-Prohibition lagers was very likely American Cluster, but given the prevalence of German immigrants in brewing, it's not much of a stretch to postulate that some German hops, or American-grown hops of German origin, would have been used as well.

Some early recipes refer to using a mix of domestic and imported hops, and the use of German hops finds further supporting evidence in early 20th-centurty Budweiser labels and advertisements, as well as ads for Coors and Piel's, which put Czech Saaz hops front and center.

For my recipe I used Cluster hops for bittering to the tune of about 29 IBUs; remember, this is a much more highly hopped lager than something like modern Budweiser, which clocks in at a mere 12 IBUs. I also added a little over 1.5 ounces of Hallertau Mittelfrüh late in the boil to give it a bit of German spicy and herbal hop aroma, which to my way of thinking will both be a great complement to the Cluster hops, and isn't a huge historical leap.

Yeast

I found very little in the way of specifics about the type of yeast that might have been used, other than the previously cited information regarding John Wagner bringing Bavarian yeast to the United States in 1840. To state the obvious, we're discussing a lager here, but I found nothing that speculated on the specific yeast strain.

I'll go out on a very short limb and say it's not much of a stretch to guess that the yeast Wagner brought with him from Bavaria was the Weihenstephan strain given the long history and prevalence of the Weihenstephan Brewery in Bavaria.

These days any clean-fermenting lager yeast, including American lager yeasts, would be suitable in this style, though if you're going for "historical accuracy" a German lager yeast -- and in my mind specifically a Weihenstephan strain such as SafLager 34/70 or CellarScience GERMAN (the latter of which I used) -- is probably best.

Interestingly, George Fix wrote in his Pre-Prohibition Pale Lager recipe, "It is usually unadvisable to use the Weihenstephan Lager strains with adjunct beers because of their low free amino nitrogen (FAN) levels (5). The malt concentration of this formulation, however, is similar to that of a standard all-malt lager, and hence the wort FAN level will be adequate for German yeast." I don't pretend to have even the smallest of fractions of the brewing knowledge of Dr. Fix but given that his recipe contains 22.5% flaked corn, I can only assume that even this relatively high percentage of adjuncts isn't enough to impact this aspect of brewing chemistry.

I was pretty anxious about making my first lager and fermenting at 50 degrees F, so even though I don't typically use yeast nutrient in my ales, I decided to give the CellarScience GERMAN a bit of help. I was originally going to use CellarScience FermFed DAP Free but that still hadn't arrived by brew day, so I wound up rushing to my local-ish brewing supply store and picking up some Fermaid O, which is similar. I dosed the wort with 4g of Fermaid O when pitching the yeast, and added another 4.5g when fermentation was about 30% complete. Supposedly the organically derived nitrogen in these types of yeast nurtients can help reduce the risk of off-flavors, and this also provides 30ppm of organic FAN which should eliminate any concerns, however minor, when using a Weihenstephan yeast strain.

Water

Brewers have had a good sense of the importance of water quality dating very far back in brewing history, and had a good handle on water chemistry by the early 1800s, but I didn't find any specific mentions of the type of water or water chemistry profile that would have been used for this style of beer.

But that line of thinking is the modern homebrewer in me. The obvious answer is that brewers probably simply used the water from the sources available to them.

That's not to say there weren't some water chemistry adjustments happening at this time. The concept of "Burtonizing" brewing water for ales by adding gypsum and other water adjustments appears in brewing literature beginning in the late 19th century, but given the cost- and labor-intensive nature of distillation or obtaining large volumes of water from other locations, it's much more likely that brewers used the water they could get in sufficient quantity from the sources closest to their brewery and did minimal or no water treatment, particularly for lagers. (Historically, and not surprisingly, the primary consideration for the location on which to establish a brewery was proximity to good brewing water sources.)

Since as homebrewers we can easily use distilled or RO water as a starting point, we have both the blessing and the curse of being able to adjust our brewing water however we see fit.

For my take on a Pre-Prohibition Lager, I used RO water and started with the "American Lager" profile in Brewfather to achieve a chloride-to-sulfate ratio of 1:1, in the hopes that this would yield a balance between the malt/corn character and the hop expression.

The End Result

The final result!

The final result!

I'm REALLY happy with how this came out. It's rich and malty, the high percentage of flaked corn adds a nice smoothness to the mouthfeel and just a hint of sweetness to the flavor. The Cluster hops give this beer a nice assertive, earthy bittering charge, and the Hallertau Mittelfrüh hops add a layer of earthy and floral aroma.

And though this isn't the greatest photo, it looks amazing. Super clear and effervescent, with a beautiful pale golden color and a fluffy white head.

This is a fantastic, easy-drinking beer, and one I'll definitely be making again! Now to ponder some tweaks for next time ...

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, borrowing from Beer Advocate, the Pre-Prohibition Lagers we're brewing today are "more nostalgic than authentic." But by grounding what we brew in historical research and period recipes, and doing our best with the ingredients and equipment we have available today, we can certainly capture the style's spirit and brew an excellent, if not 100% historically accurate, Pre-Prohibition Lager.

Cheers!

Resources

- American Handy-Book of the Brewing, Malting and Auxiliary Trades, Robert Wahl and Max Henius, 1901

- 2021 BJCP Style Guidelines: Historical Beer: Pre-Prohibition Lager

- America's Founding Lagers: The Pre-Prohibition Landscape, Michael Stein

- Recipe: Draught Beer 1912 Pre-War Lager, Paul Kaiser and Michael Stein

- Pre-Prohibition Lager: A Classic American Pilsner-Type Beer, Gordon Strong

- Explorations in Pre-Prohibition American Lagers, George J. Fix

- Pre-Prohibition Lager: More Nostalgic Than Authentic, Don Russell

- Video Tip: The Story of Pre-War Pils, Chip McElroy and Dusan Kwiatkowski

- Brülosophy: Short & Shoddy Pre-Prohibition Lager, Will Lovell

- We Want Beer! Back to the Future with Pre-Prohibition Lager